By: Gabriel Cesarini

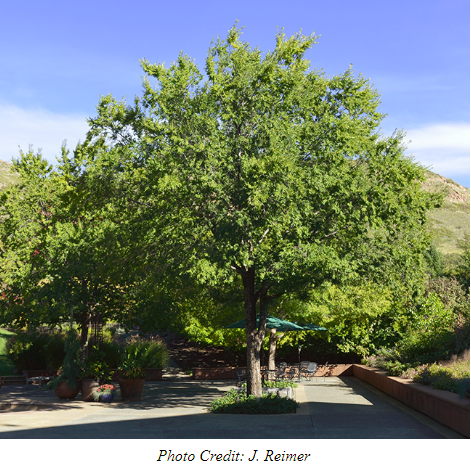

Ulmus parvifolia, commonly known as Chinese elm or lacebark elm is a deciduous tree species native to eastern Asia, specifically China, Korea, and Japan. Although Chinese elms prefer rich and moist loam soil types, they grow in a variety of soils that range from wet to dry and also urban conditions. Chinese elm survives in USDA Hardiness Zones 4-9. They are small to medium trees that typically grow up to 70 feet tall with a graceful, upright, wide spreading crown formed by the trees fine pendulous branches. Chinese elm is known to usually be resistant to Dutch elm disease as well as phloem necrosis, and pests like elm leaf beetle and Japanese beetle.

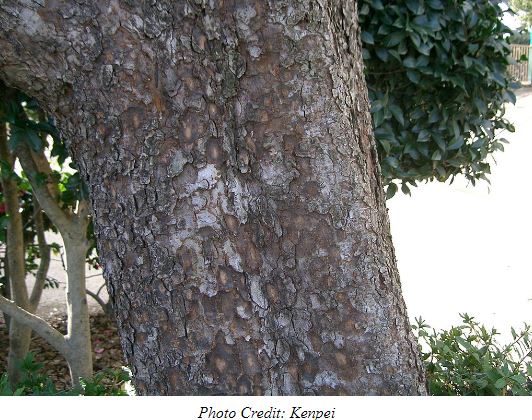

Chinese elms often grow in the typical elm vase shape. Their showy bark exfoliates to reveal unique patterns and tones of brown, orange, and grey. This novel characteristic adds to its visual appeal, especially during winter. Chinese elm leaves are medium sized (2-3 inch long), dark green, shiny, and leathery. Trees located in cooler regions experience a change in color of leaves to beautiful shades of red, yellow, and purple. Chinese elm fruit are a flattened, winged samara about ½ inch long that is brown and notched at the top, occurring in clusters in the fall.

Chinese elm is a popular tree species used for Bonsai, which is a Japanese form of art practiced by growing and pruning trees in small containers. The reason for this is due to its species abundance and its ability to handle a wide range of conditions like temperature, humidity, and light. Chinese elms make for great street, median, and parking lot trees as long as they are pruned correctly during youth and adolescence. These trees could afford to be planted more within their hardiness zones due to their high tolerance to a wide range of conditions, resistance to typical elm downfalls, and novel qualities.

All photos and references are used for educational purposes only.

References

- Gilman, Edward F., & Watson, Dennis G. “Ulmus parvifolia -- Chinese Elm” hort.ufl.edu. University of Florida, October 1994. Web. 11 December 2017 <http://bit.ly/2B9vC0X>

- "Ulmus parvifolia Fact Sheet.” Virginia Tech Dendrology. Virginia Tech Dept. of Forest Resources and Environmental Conservation, 2017. Web. 11 December 2017. <http://bit.ly/2BA4jNG>

- “Ulmus parvifolia.” Missouri Botanical Garden. Missouri Botanical Garden. Web. 11 December 2017. <http://bit.ly/2a7z1M7>

Photos

- Reimer, J. “Ulmus parvifolia ‘Allee’.” selectree.calpoly.edu. Cal Poly. Digital Image. 11 December 2017. <http://bit.ly/2AuxfXw>

- Kenpei. “Ulmus Parvifolia.” Wikimedia Commons. Wikimedia Commons, 27 December 2006. Digital Image. 11 December 2017. <http://bit.ly/2BdQEv8>

- “Ulmus parvifolia leaf.” Virginia Tech Dendrology. Virginia Tech Dept. of Forest Resources and Environmental Conservation, 2017. Digital Image. 11 December 2017. <http://bit.ly/2BU2iIm>

- “Ulmus parvifolia fruit.” Virginia Tech Dendrology. Virginia Tech Dept. of Forest Resources and Environmental Conservation, 2017. Digital Image. 11 December 2017. <http://bit.ly/2C75m4S>

- “Ulmus parvifolia twig.” Virginia Tech Dendrology. Virginia Tech Dept. of Forest Resources and Environmental Conservation, 2017. Digital Image. 11 December 2017. <http://bit.ly/2AdnlVM>

- Ross, Sage. “Chinese elm bonsai 111.” Wikimedia Commons. Wikimedia Commons, 24 December 2008. Digital image. 11 December 2017. <http://bit.ly/2B7Gr3a>